Bad Machinery: Managing Interrupts Under Load

Preamble and tl;dr

Teams that have both a project and operational load usually have an idea of how much of each type is acceptable. 50% is the example in SRE as a good number for the maximum amount of time that should be dedicated to operational load.

Lots of teams get very good at handling tickets and oncall. The real challenge is doing this so you don’t stress people out and carve out “make time” (i.e. time spent on more creative tasks or projects) for them.

double-meta-tl;dr-bullet-points:

- Each day, try to do either projects or interrupts, not both.

- If you’re oncall, don’t try to do projects, and vice versa.

- People aren’t machines, context switches are really expensive, and usually assumed to be free in process planning.

- People who are constantly interrupted end up with delayed and sloppy project work, and vice versa (people who have a lot of project work are sloppy at interrupts unless time is carved out for them).

- Your team’s oncall and interrupt-handling should be structured around funneling interrupts at the people who are supposed to be interrupted.

- If that’s too much for those people, add more people until it isn’t. “Spreading the load” by assigning items across the entire team randomly is counter-productive.

What is “Operational Load”?

Operational load takes many forms, some more obvious than others. For the sake of this document, we define “Operational Load” on a team as:

- Pages

- Production pages and their fallout, dealing with production emergencies.

- Pages can sometimes be monotonous and recurring, requiring little thought. They can also be engaging and involve tactical in-depth thought. You don’t know which is which until you look.

- Pages always have an expected response time, sometimes measured in minutes.

- Tickets

- Customer requests, for which someone has to do something.

- Tickets, like pages, can be either simple and boring or require real thought.

- Simple: Code reviews for a config the team owns.

- Non-Simple: Bespoke request for help with a design/capacity plan.

- Tickets may also have an SLA

- Ongoing Responsibilities

- AKA “Kicking the can down the alley”.

- Example: Code or flag rollout the team is responsible for.

- Example: Responding to ad-hoc time-sensitive questions from customers.

- May not have an SLA as such, but can interrupt someone.

For certain purposes, you can think of operational load as “Something that can interrupt someone at a non-specific time, and requires them to look at it to determine if it can wait”.

Managing Operational Load

There are a number of existing methods for managing operational load at the team level.

- Pages

- By far the most common means of managing pages is to have a dedicated ‘primary oncall’. This is a single person who manages pages and responds.

- Primary may also be responsible for tickets, depending on ticket load. It is also usually the primary’s responsibility to manage client communications, escalation to developers, and so on.

- Usually there is a ‘secondary oncall’, acting as a backup for the primary.

- Secondary duties vary: they may be responsible for tickets. In some rotations, the secondary’s only duty is to contact the primary if pages fall through. Depending on this, they may consider themselves ‘on interrupts’ or not, depending on duties.

- Oncall person may escalate to another team member if a problem is not well understood.

- Tickets

- This is managed in a number of different ways:

- Example: Primary oncall does tickets while oncall.

- Example: Secondary oncall does tickets while secondary.

- Example: Dedicated non-oncall ticket person.

- Example: Tickets are randomly assigned to entire team.

- Example: No auto-assignment, team is expected to service tickets ad-hoc.

- Ongoing Responsibilities

- Flag flips, pushes, ongoing engagements, user interrupts, etc.

- Sometimes these get done by the oncall (pushes, flag flips, etc).

- Sometimes each of these get assigned ad-hoc (‘feature buddies’).

- Sometimes an oncall person picks up a lasting responsibility (i.e. a multi-week rollout or ticket that lasts beyond their shift week).

The Story So Far

This document as a whole is somewhat Google-centric, and may contain assumptions about your service or team that are untrue. For example, you may be lucky enough to have a staffed secondary who can back you up as the oncaller, or you may have varying degrees to which you can effect change.

Factors in Determining how Interrupts are Handled

Taking a step back for a second, there are a number of metrics that factor into how each of these interrupts are handled. I’ll attempt to list them here (sorry, I like bulleted lists):

- Interrupt SLA or expected response time.

- The number of interrupts that are usually backlogged.

- The severity of the interrupts.

- The frequency of the interrupts.

- The number of people available to do a certain kind of interrupt (i.e. some teams require a certain amount of ticket work before being oncall).

The closest thing to a problem statement you’re getting

One thing you might notice about these is that they’re all suited to meeting the lowest possible response time, without factoring in more human costs. Trying to take stock of the human cost and productivity cost is difficult, so of course, we can only be as non-vague as we can in setting these out.

Humans are Bad Machinery

Humans are bad machinery. They get bored, they have processors (and sometimes UIs) that aren’t very well-understood, and aren’t very efficient. Recognising that this is “Working as Intended” and trying to work around or ameliorate how humans work could fill volumes -- for the moment we’ll settle for some basic ideas that might be useful when determining how interrupts should work.

Cognitive Flow State

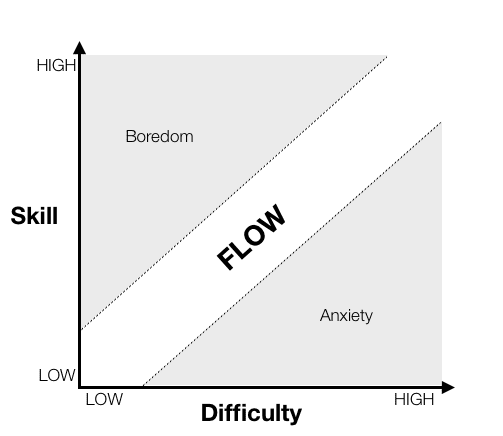

The concept of “Flow State” is widely accepted and can be empirically acknowledged by pretty much everyone that works in Software Engineering, Sysadmin, SRE, or quite a few other fields. Being in “The Zone” can increase productivity, but can also increase artistic and scientific creativity, and encourage people to actually master and improve on the task or project they’re working on. While in this state, being interrupted can end it, if the interrupt is disruptive enough. We want to maximise the amount of time spent in this state.

Cognitive Flow can also apply to less creative pursuits where the skill level required is lower, and the essential elements of flow can still be fulfilled (clear goals, immediate feedback, a sense of control, and the associated time distortion). Think housework, or Angry Birds.

So, we can think of investment in getting into a state of “Flow” to be fixed per period of cognitive flow, once the position on the graph doesn’t drastically change. So, you don’t get ‘In the Zone’ by working to solve a really hard programming problem, then get up, high five your co-worker and go tidy your desk because you’ve been meaning to. It applies to related close-by areas on the plane.

Cognitive Flow State: Creative and Engaged

This is the “Zone”. You’ve been working on a problem for a while, you’re aware of and comfortable with the parameters of the problem, you feel like you can fix it or produce it, and you work at it, losing track of time and ignoring interrupts as much as possible. Maximising the amount of time a person can spend in this state is very desirable -- they’re going to produce creative results, do good work by volume, and they’ll be happier at the job they’re doing.

Unfortunately, a lot of people in roles with a meaningful operational component (like SRE) spend a lot of their time either trying and failing to get into this mode and getting frustrated at it not happening, or never even trying, and languishing in the interrupted state. Oh, speaking of which:

Cognitive Flow State: Angry Birds

People enjoy doing things they know how to do. In fact, it’s one of the clearest paths to cognitive flow. Some of the most motivated people you can meet in SRE are oncall at the time -- it can be very fulfilling to chase down the causes of problems, work with others, and improve the overall health of the system. Conversely, most stressed-out oncallers are stressed out either by pager volume, or because they’re treating oncall as an interrupt. They’re trying to code or work on projects, while being oncall or on fulltime interrupts. They exist in a state of constant interruption, (or interruptability). This is extremely stressful.

On the other hand, when a person is concentrating full-time on interrupts, they stop being interrupts. At a very visceral level, doing incremental improvements to the system, whacking tickets, fixing problem and outages becomes a clear set of goals, boundaries, and clear feedback (you close X bugs, or you stop getting paged). All that’s left is distractions. When you’re doing interrupts, your projects are a distraction.

Do One Thing Well

If you’re still reading, you might be wondering about the practical implications.

The following suggestions are mainly for the benefit of team managers or influencers. This document is agnostic to personal habits - people are free to manage their own time as they see fit. The concentration here is on directing the structure of how the team itself manages interrupts, such that people aren’t set up for failure just by virtue of team function or structure.

Distractibility

Here’s an example from SRE. Let’s take a random SRE called Sam. Sam comes into work on Monday morning. Sam isn’t oncall or on interrupts today, so they would clearly like to work on their projects. They grab a coffee, stick on their “do not disturb” headphones, and sit at their desk. Zone time, right?

Except, at any time, one of the following things might happen:

- Sam’s team uses a tool that randomly assigns tickets to team members. A ticket gets assigned to Sam, due today.

- Sam’s colleague is oncall and gets a page that doesn’t have a playbook entry and requires her to interrupt Sam, since it’s Sam’s area of expertise.

- A user of Sam’s service raises the priority of a ticket that’s remained assigned to Sam since last week, when they were oncall.

- A flag rollout that’s rolling out over 3-4 weeks and that Sam is the assigned consultant for goes wrong, forcing them to drop everything to look, roll back, etc.

- A user of Sam’s service contacts Sam to ask a question, since Sam’s usually very helpful.

- etc. etc.

The end result here is that even though Sam has the entire calendar day free to work on projects, they remain extremely distractible. Some of these distractions they can manage themselves (close email, turn off IM), while some are caused by policy, or by assumption around interrupts and ongoing responsibilities.

It can be claimed that some of this is inevitable and by design, and that’s correct -- people do hang onto bugs that they’re the primary contact for, and build up responsibilities and obligations. However, what we’ll concentrate on here is ways that interrupt response can be managed on a team, so that more people (on average) can come into work in the morning, and feel undistractible.

Polarising Time

The basic gist of what we should try to do is minimise context switches. Some interrupts are inevitable. However, the general model of an engineer as an interruptible unit of work, whose context switches are free, is suboptimal if we want people to be happy and productive. Assign a cost to context switches. If someone is working on a project, and gets interrupted for 20 minutes, that is two context switches and probably a couple of hours of really productive work lost – further reading from the APA suggests that the amount of time lost, or slowdown in progress on the tasks being switched between can scale by task complexity. So, if both oncall and a person’s project work are mentally taxing, the impact of context switches is compounded overall.

The ideal here is polarised time between work styles, with a period of as long as possible (ideally a week, but a day or even a half-day may be more practical. This also fits in with the complementary concept of ‘make time’).

What this means is (if you wanted a soundbite) that when a person comes into work each day, they should know if they’re doing just project work, or just interrupts. Polarising their time in this way means they get to concentrate for longer periods of time on the thing they’re doing, and they don’t get stressed out because it’s not the thing they’re supposed to be doing.

Seriously, tell me what to do

Okay, if the general model doesn’t work for you, here are some specific suggestions.

General suggestions

For any given class of interrupt, if the volume is too high for one person, add another person. This most obviously applies to tickets, but can potentially apply to pages, too -- the oncall can start bumping things to their secondary, or downgrading pages to tickets.

Oncall

The primary oncall person should be doing just oncall. If the pager is quiet for your service, then doing tickets or other interrupt-based work that can be abandoned fairly quickly should be part of their duties. When you’re oncall for a week, you write that week off, as far as project work is concerned. If a project is too important to be let slip by a week, then that person shouldn’t be oncall. Escalate. A person should never be expected to be oncall and also make progress on projects (or anything else with a high context switching cost).

Secondary duties depend on how often the secondary is called upon now now. If the function of the secondary is to find the primary if an alert isn’t responded to by the primary oncaller, then maybe we can safely assume they can do project work. However, if there’s a separate ‘tickets’ person that’s not the secondary, consider merging. If the secondary is expected to actually help the primary when the pager gets spammy, they should do interrupt work, too.

(Aside: You never run out of interrupt work. Your ticket count might be at zero, but there are always playbooks that need updating, configs that need cleanup, etc. Your future oncallers will thank you, and it means they’re less likely to interrupt you during your precious make time).

Tickets

If you currently assign tickets randomly to victims on your team, stop.

Tickets should also be a full-time role, for an amount of time that’s manageable for a person. If you happen to be in the unenviable position of having more tickets than can be dealt with by the primary and secondary oncall combined, then assign another fulltime tickets person. Don’t ‘spread the load’ across the entire team. People are not machines, and you’re just causing context switches that impinge on valuable flow time.

Ongoing Responsibilities

As much as possible, define ‘roles’ that can have their mantles taken up by anyone. If there’s a well-defined procedure for doing and verifying pushes or flag flips, then there’s no reason a person has to shepherd that change for its entire lifetime, even after they stop being oncall or on interrupts. Define a ‘push manager’ role who can juggle pushes for the duration of their time oncall or on interrupts -- formalise the handover process. It’s a small price to pay for uninterrupted make time for the people not oncall.

Be on interrupts, or don’t be

Sometimes when a person isn’t on interrupts, an interrupt comes in that only they can deal with. First of all, this shouldn’t be the case -- but sometimes it is. You should work to make this rare.

Another case that’s spotted sometimes is people who do tickets when they’re not on tickets, because it’s an easy way to look busy. This is not helpful. It means the person is less effective than they should be, and they skew the numbers in terms of how manageable the load is. If there is one person on tickets, but there are always two or three people also taking a stab at the ticket queue, then you might still have an unmanageable ticket queue, but you just don’t know it.

The assumption I’m making is that this is an issue that needs to be addressed, and may be a hidden management problem – the more this happens, the more unpredictable your project delivery estimates and assurances get.

Reducing Interrupts

If there are too many people on the team at any given time that need to do interrupts, you may get to a point where your interrupt load gets unmanageable. There are a number of techniques you can use to reduce your ticket load overall.

Actually Analyse Tickets

Lots of ticket rotations or oncall rotations act like a ‘gauntlet’. This is especially true of rotations on larger teams. If you’re only on interrupts every couple of weeks, it’s easy to ‘run the gauntlet’, say ‘Phew, that’s over’, and get on with whatever you were doing. Your successor then does the same, and the root causes of tickets don’t properly get looked at -- it’s just lots of people getting annoyed by the same thing in succession, when there should be forward movement.

There should be a handoff for tickets, as well as for oncall. The format is less important tha the state capture – mostly it involves setting out the state of each ongoing issue, and some context to allow the next oncaller to (for example) expect a certain type of issue, so their response to it is perhaps more timely or less stressful. This will maintain shared state between ticket handlers as responsibility switches over. Even some basic introspection into what the root causes of interrupts are can provide good solutions for reducing the overall rate. Lots of teams do oncall handoffs and page reviews. Very few teams do this for tickets.

You should have a regular ‘scrub’ for tickets and pages, where you take certain classes of interrupts and see if you can identify a root cause. If you think the root cause is fixable in a reasonable amount of time, then silence the interrupts until the root cause is expected to be fixed. This provides relief for the interrupts person, and a handy deadline enforcement for the person fixing the root cause.

Respect yourself as well as your customers

This applies more to user interrupts than automated ones, although the principles stand. If tickets are particularly annoying or onerous to do, you can effectively use policy to make things a little easier.

Remember:

- Your team sets the level of service provided by your service.

- It is okay to push back some of the effort onto your customers.

- 99% of user tickets require one of (a) Your Knowledge or (b) Your Privileges. Target (b) for automation first (but don’t forget (a)!. This can also be addressed by education or product improvements.

If there is a particular thing your team is responsible for doing that involves doing tickets or interrupts for customers, you can often use policy to make things easier, or more manageable. This can be temporary or permanent, depending on what makes sense, and has a good balance between respect for the customer, and respect for yourself. Policy can be as powerful a tool as code.

For example, if there is a particularly flaky thing you support, that maybe doesn’t have a lot of development time dedicated to it, and there are a small number of needy customers who use it, consider other options. Think about how valuable the time spent on doing interrupts for this system is, and whether it’s the right way to be spending time. At some point, if you’re unable to get the attention you need on fixing the root cause of the problems you’re getting interrupts about, maybe the component you’re supporting isn’t that important, and you should consider more drastic options such as adjusting its SLO, deprecating it, replacing it, or other things that might make sense. Not all of these options may be available to you, of course – but getting to this point is an indication that the status quo shouldn’t continue.

If there are particular steps in a certain kind of interrupt that are time-consuming or tricky, but don’t require having your privileges to do, consider also using policy to push that back onto the requestor. For example, if people need to donate resources, prepare a CL, or do some other step, get them to do it and send it for your review. Remember that it’s the customer that wants something done, and they should be prepared to spend some effort on getting what they want.

A caveat to all of this is that you need to find a balance between respect for the customer and for yourself. The guiding principle here is that the request from the customer should be meaningful, rational, and give you everything you need to fulfil it, and your response should be helpful and timely.